Biography

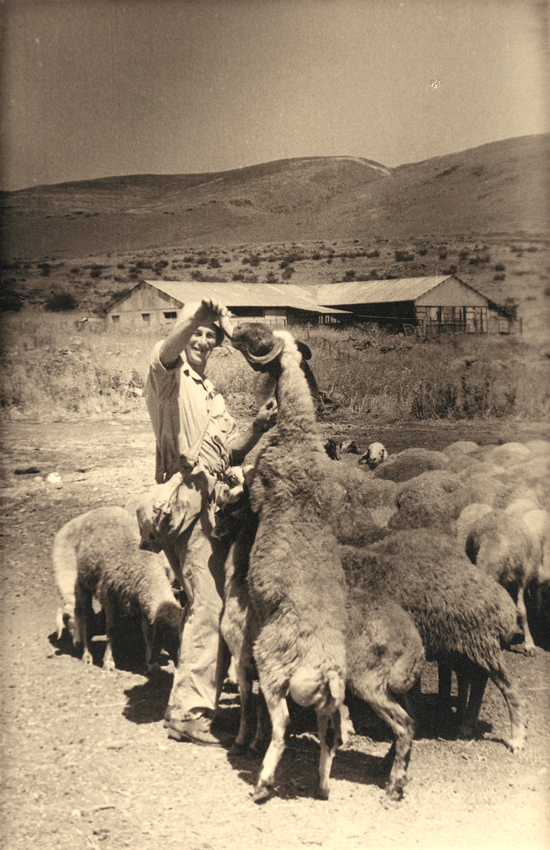

Moshe Kagan was born in 1922 in Kremenets in Poland, immigrated to Israel in 1948, joined Kibbutz Shamir, and devoted himself to work at the sheep barn.

He participated in most of the exhibitions of The Israel Painters and Sculptors Association and The Association of Painters and Sculptors of the Kibbutz Haartzi.

He exhibited his art in dozens of solo exhibitions in Israel and abroad: in Tel Aviv (1962, 1976, 1968), in New York (1967), in Switzerland (1976), etc. His works are in private collections in Israel and abroad.

He won the Deborah Davidson Scholarship.

Moshe Kagan illustrated several books, including Haim Canaani’s book “Kibbutz Shamir in the War of Independence”.

He established an antiquities museum in his kibbutz.

The art of Moshe Kagan

Daphna Shapira-Hasson

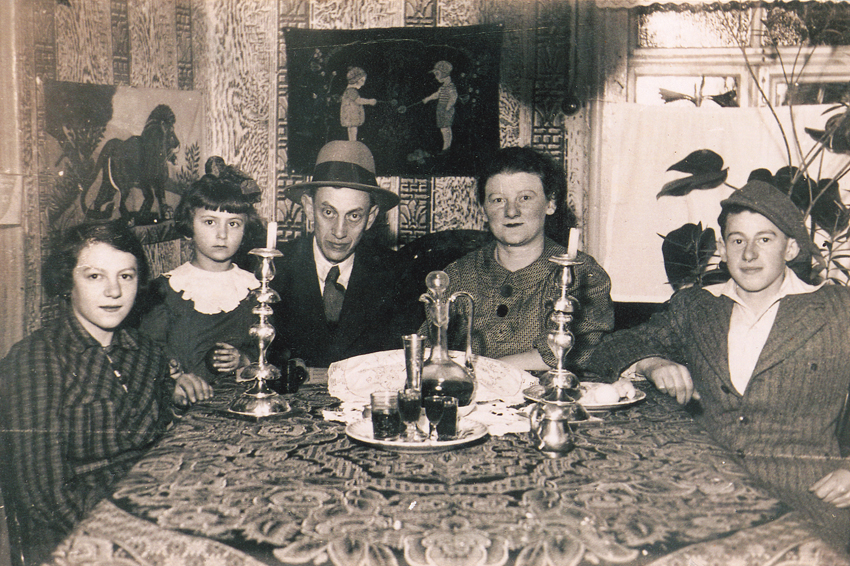

“I am the most fortunate artist alive,” affirms the artist Moshe Kagan, whose life has taken him from the total destruction of his childhood home and family in Poland to the pastoral beauty of his life in Kibbutz Shamir at the foot of Mount Hermon.

The tension between the “there” of the Shoah, and the “here” of life in Israel is what lies at the base of Kagan’s art. The hours he spent as a shepherd with his flock of sheep in the Galilee hills moved him to draw the landscape set before him. These were his happiest hours. As a young boy he suffered from disease and hunger as a refugee in Russia, and later as a soldier in the Free Polish Army he witnessed the horrors of the Warsaw ghetto and the devastation of Berlin, discovering at the end of the war that his entire family was lost to him. His time in the hills, watching his sheep, was another world, a complete contrast to this former life.

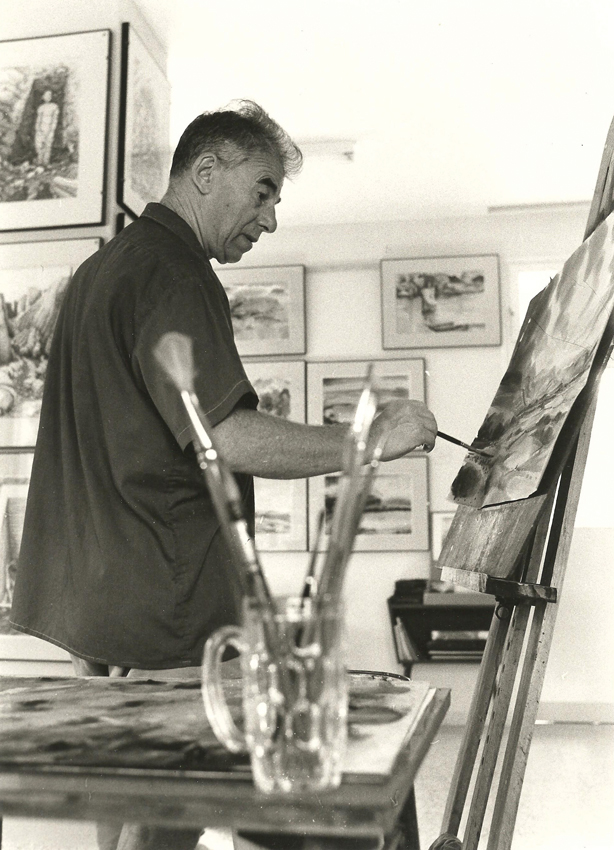

Here: The watercolors

The dozens of watercolor landscapes of the Galilee, glowing with a kind of tender light, show moments of passing enchantment. These are the “here” of Kagan’s art. Here is Kibbutz Shamir, which became Kagan’s chance for a new beginning, with the freedom to wander in nature and to paint. The lucidity and the clarity of nature, as well as the shining white paper underneath the paint, together create the lyricism of his work.

Israeli artists whose style was labeled “abstract lyricism” are characterized by their watercolors of the Israeli landscape. This group, which includes Shtreichmann, Zaritsky, and Steimatzky, as well as the group known as “the walkers to the Kinneret” – Holzman, Avniel, Guttman – all painted in watercolor. “The tradition of abstract lyrical tends toward the aquarelle – a view out of the window toward the air and the light which calls for its unique qualities.”

Watercolor, the material itself and the way it is used, is most often identified with one of Kagan’s main subjects – the Kinneret. The relationship of the different natural elements – the mountains, the vegetation, and the water – can be compared to the relationship of the materials of the painting. There is the same search for air and light as material elements which appears in the central image of water in Kagan’s paintings, as the subject, and in the physical properties of the paint, as the material. This search for air and light, in both the physical and the metaphysical, is identified with the mystical/Romantic school of watercolor in. 19th-century English painting, and in the Chinese watercolors imbued with Buddhist and Taoist values.

English Romantic watercolors expressed through their technique “lyrical intuition” or “mystical communication”, while the Chinese viewed the technique as expressing the supreme importance of water as “the most sublime force of life, giving sustenance without effort, flowing in places that humans rejected, thus showing its similarity to the Tao.”

Water as the source of life and rebirth is present at the center of most of Kagan’s watercolors. Kagan’s technique allows light and air to express his own rebirth, creating an unmediated connection between the artist and nature. His technique of working on wet paper allows the water to flow spontaneously, combining action with inaction, simplicity with complexity, in exactly the same way as the Tao: “Look – you can’t see, since it’s beyond shape; listen – you can’t hear, it’s beyond sound; reach out – you can’t catch it, it’s beyond form; experience without action, work without doing, see simplicity in complexity, achieve greatness in the small things.”

The qualities of water – transparency, lack of defined boundaries, serenity – appealed to the Taoist as indicative of moral qualities: gentleness, complacency, frugality, lack of ego. This explains the lack of human figures in Chinese painting; in Kagan’s watercolors as well, the human figure seldom appears. When it does appear, it is as an expression of the merging of the artist with nature, a renunciation of the artist’s ego.

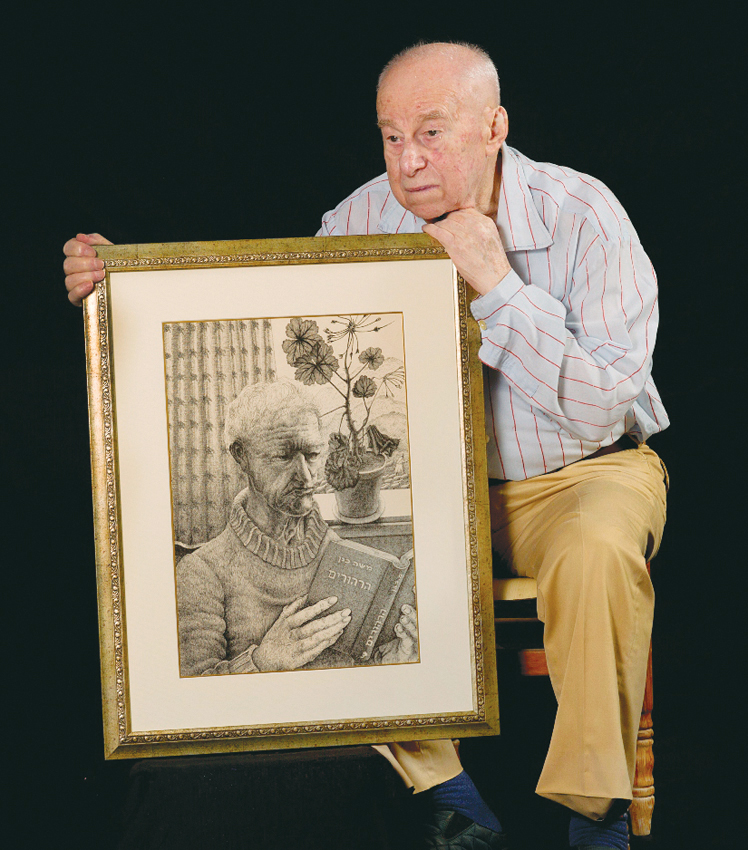

There: Illustrations of pain and loss

The artist’s occupation with “there” began only in 1967. Until then, Kagan produced only landscapes, based on direct observation or on memory. The Six Day War, however, opened a floodgate of memory and pain in the artist, and he produced a large body of work based on his memory of life “there”, which he defined as “problem-solving paintings”.

These are compressed sketches done with a black Rapidograph pen on white paper. Each sketch tells a specific story, whether of an historical incident or of a personal memory. This body of work is completely different from his watercolors and landscapes; they contain human figures and are full of memory and pain.

The style of these works suggests engraving: a collection of meshed lines make up the figure, whether human, animal, or material. The forms are defined and the sketch tells a story. Galia Bar-Or, in her study of Holocaust survivors who attempted to work through their memories by illustrating them, argues that the detachment from the personal story created a detachment in Israeli society, and the story-telling is a way to renew the connection between experience and reality. “The story is like seeds stored in airless pyramids for thousands of years.” If the watercolors are depictions of “light and air”, these are pictures of “darkness and pain”. Here Kagan confronts the horrors of the past and tries to come to grips with the pain. These pictures deal with the loss of Polish communities in the Holocaust (“Warsaw Ghetto – Tefillin”; “Shoah”); the experience of general and personal pain – loss of his son in a traffic accident, death of a soldier in war, death of a bird in the window (“Portrait”; “Requiem 1”; “Requiem 2”; “Pigeon Injured by a Shell”; “Traffic Accident”; “The Crucified”); protest and criticism of the Catholic Church during the Holocaust (“The Sick Tree”); Stalin and his machinery of death (“Stalin, Architect of Socialism”); and the terrors of war in Israel (“Children’s Kindergarten”; “Shelter”).

It seems that all the pain of the past finds its expression in random incidents in the present, which are weighted with the bereavement and sorrow from all the personal and national losses the artist has experienced.

In contrast to Kagan’s bright and optimistic “here”, symbolizing, as it did for Israeli artists of the 1920’s, a new start in a land of air and light, his “there” is dramatic, surrealistic, dark and painful, expressive of the dark and painful past of the Jews which the same painters of the 1920’s tried to repress from their work. Very few artists in the first half of the 20th century attempted to tell the dark story of the lost communities of Europe, and those who did were rejected by the Israeli art establishment. Jacob Steinhardt and Yosef Bodko, in the 1930’s, created a figurative expressionism in black and white, whose subject was the history of the Jews in Europe. The critics of the time characterized their work as “a depiction of Jewish life in the shtetl from before the First World War. Apocalyptic German Expressionism has been converted into a pathos-filled portrayal of the misery of Jewish life.”

In Moshe Kagan’s work, Jewish life does not appear as “pathos-filled misery”; the figures are more Israeli-like and expressive, but the type of drawing corresponds to the depth of despair and pain of the Diaspora, and thus was not received favorably in Israel. “The Israeli bourgeois artistic canon is clean and free of blemishes, ‘healthy’, with no malignant memories of a past life of exile and otherness.” Pain of the past is perceived as “otherness”, and therefore must be denied and suppressed, although this denial eventually separates the man and the culture from their true identities.

“We who have witnessed and experienced the horrors in Europe must not renounce our past. We must instead remember it, while starting afresh, healing our souls – simply by being born anew.” These words echo in our examination of the great difference between the work of Moshe Kagan and those of the group of artists opposed to him. There exists the desire to forget and to close off and to focus instead on the future, on the one hand, and the compulsion to remember and to connect to memories of families and of loss, on the other. Kagan’s rebirth on the kibbutz, sunlit and colorful, lifted out of the darkness, is nonetheless assaulted by the nightmares of the past. This body of Kagan’s work returns the gaze, in both senses – the gaze toward the personal, repressed past of the artist himself, and the gaze into the repressed abyss of Israeli culture and art.

Mosaic – Synthesis of the Past and the Present

Another body of work highlights an additional aspect of the “here” for Kagan – his mosaics. Kagan created his first mosaic on the wall of the kibbutz dining hall in 1958. The 1950’s saw a large body of mosaic work in public spaces in Israel, as part of the perception of art as a social force opposing the influence of bourgeois values usually assigned to objects of art. This was an attempt to dismantle the “traditional relationship between the art object and the viewer, and to create an artistic space not measured by capital or property.” Kagan’s mosaic wall in the kibbutz dining hall depicts daily life in the kibbutz, and represents, through its public dimensions, Kagan’s position as a kibbutz artist, living the socialist way of life upon which he was raised as a youth in the Shomer ha-Tza’ir movement in Warsaw after the war.

Kagan returned to work in mosaics only in old age, although this medium is connected to his arrival at Kibbutz Shamir and his wanderings in nature which led him to archaeological findings in the fields and the founding of the archaeological museum on the kibbutz. Kagan’s rapport with nature and his familiarity with its every aspect – both above ground as expressed in his watercolors, and below ground as shown in his archaeological findings, drew researchers of nearby “Tel Anafa” to dedicate their book about the site to him.

The mosaic work is also connected to the “Canaanite” movement in Israeli art, which was influenced not by the Jewish past, but by the ancient history of the land itself. “The Canaanite movement draws its inspiration from the primal connection of Israeli youth to the land itself, to its archaeological sites and to its landscape…In wandering the land, the Israeli youth synthesizes urban values with those of the topography, the flora and fauna of the land, as well as of the past and the present.”

Kagan states that he “divorced” himself from religion at an early age. His connection to the land and to its history was therefore translated into his artistic life. Here, as in the watercolors, the affinity to the land becomes a material element of his art – the stones and glass pieces of the mosaic, which he collected during his nature explorations. The structure of the mosaic, in which the image is constructed of many pieces, brings to mind Kagan’s need to search the past, to create a “life picture” from many different strands of memory, coming together in the work – the lone stone which creates, together with other stones, one large picture.

Notes:

1) From a conversation with the artist, Dec. 2013.

2) Gideon Ofrat, the Artistic Medium, 1987, pp. 21-23.

3) Galia Bar-Or, Hebrew work: Israeli art from the 1920’s to the 1990’s, Ein-Harod, 1998, pp. 48.

4) Tamuz, Levita, Ofrat, The story of Israeli art from Bezalel until today, Tel-Aviv, 1980, pp. 93. Ofrat, pp. 22

5) Oz Almog, Portrait, pp. 145 (from the testimony of a new immigrant, Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk, 1947)

6) Tali Tamir & Yonatan Simon, Double portrait, Tel-Aviv Museum of Art, 2001, pp. 77

7) Anat Kedar, Thoughts: the life of Moshe Kagan. pp. 39.

8) Sharon C. Herbert, Tel Anafa, University of Michigan

9) Tamuz, Levita, Ofrat, The story of Israeli art from Bezalel until today, Tel-Aviv, 1980, pp. 93. Ofrat, pp. 144